Inspiration February 16, 2017

In our ongoing series #WomenThatDid, ENTITY profiles inspirational and famous women in history whose impact on our world can still be felt today. If you have a suggestion for a historical powerhouse you would like to see featured, tweet us with the hashtag #WomenThatDid.

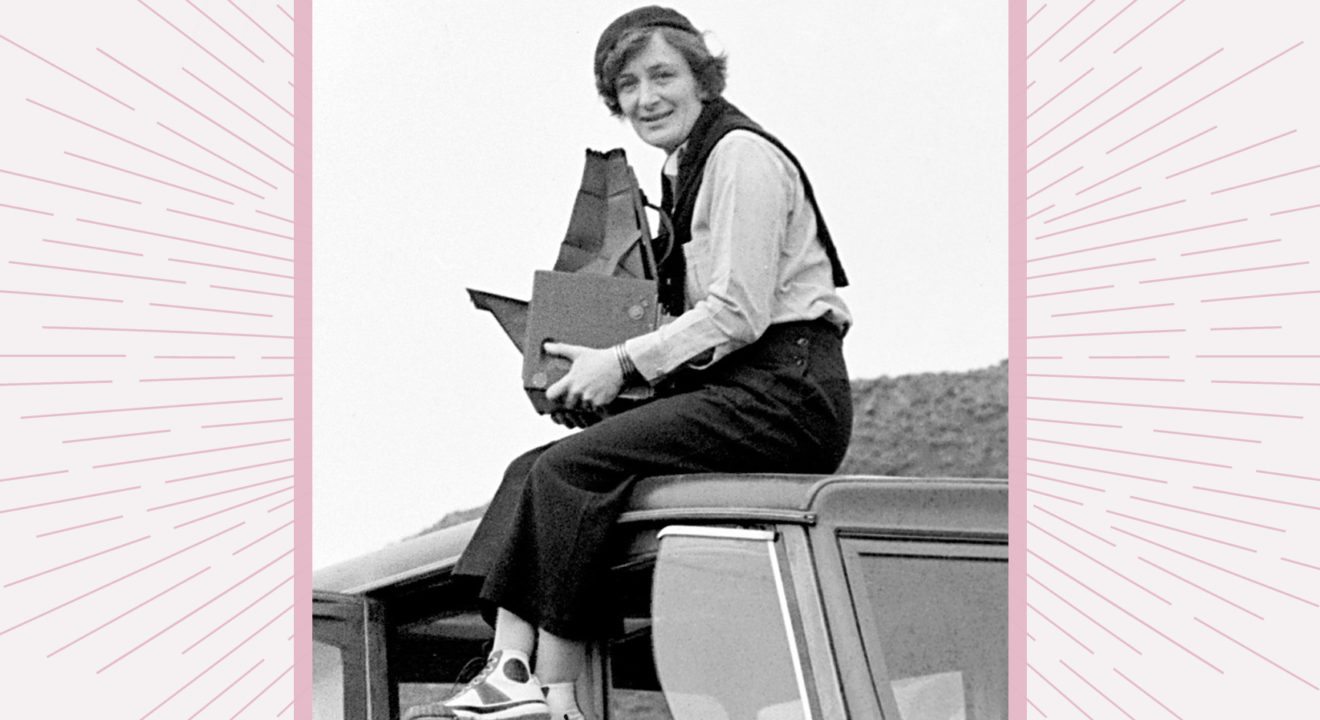

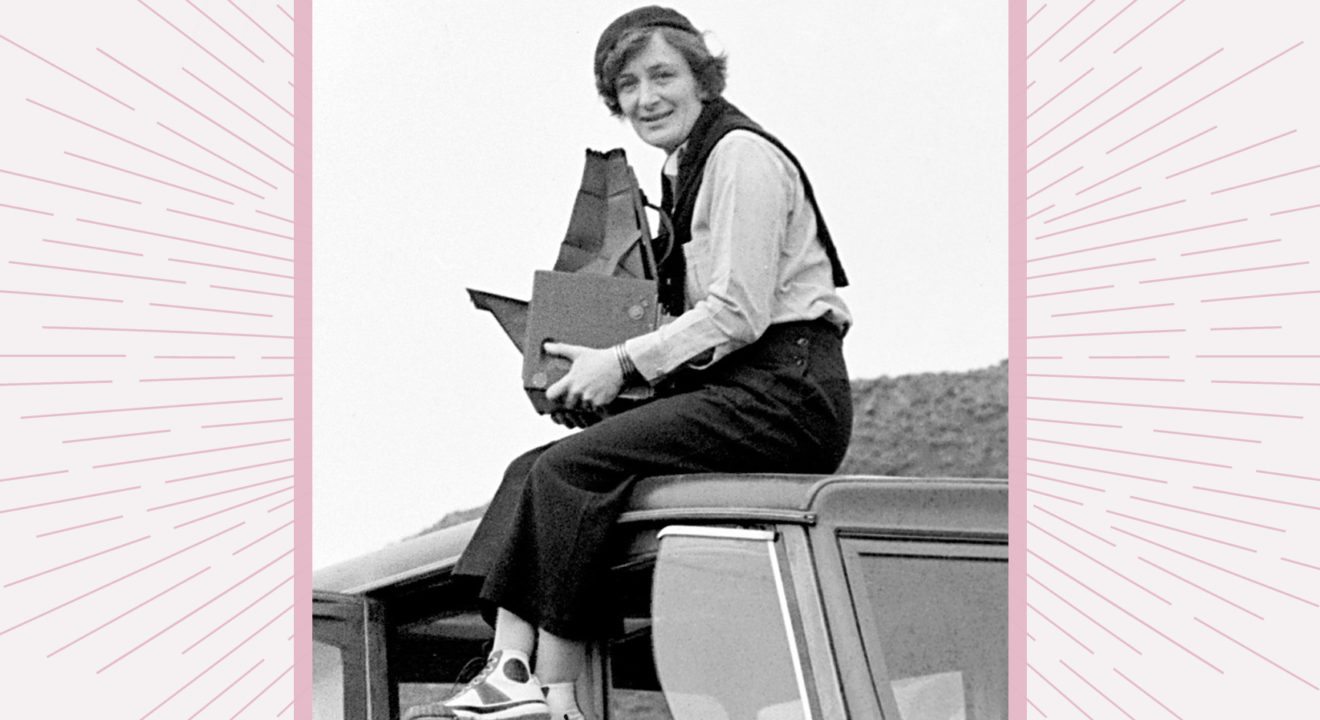

Name: Dorothea Lange

Lifetime: May 26 1895 – October 11, 1965

What she’s known for: Dorothea Lange is best known for her documentary photography and photojournalism. Throughout Great Depression, Lange worked with the Resettlement Administration (RA) and the Farm Security Administration (FSA). Her photos humanized the consequences of the Great Depression and influenced the birth and growth of documentary photography as an art style.

Why we love her: At a young age, Lange was doubly traumatized when she contracted polio at seven and then again when her father abandoned her family when she was 12. The polio left her right leg significantly weakened and she walked with a limp because of it. Of it she said, “It formed me, guided me, instructed me, helped me, and humiliated me. I’ve never gotten over it, and I am aware of the force and power of it.”

She studied photography at Columbia University and apprenticed with several successful studios in the city. After a year, she decided to travel the world, but her trip was cut short in San Francisco when she was robbed. She set up shop in San Francisco, and opened a successful portrait studio business.

In 1920 she married the noted painter Maynard Dixon, and she gave birth to their two sons. In 1935 she and Dixon divorced and she married economist Paul Schuster Taylor the same year. When the Great Depression hit, she began shooting street photography. Her photo “White Angel Breadline” captured other photographer’s attention and she signed on to work with the RA and the FSA because of it.

She and Paul documented rural poverty and the exploitation of the sharecroppers and the migrant workers. Her husband gathered economic information and Lange would photograph them. Her most famous photograph, “Migrant Mother,” was shot in 1936 and captured the family’s loss of hope for the future. When the photo became a national sensation it made the public realize the impact unemployment had on entire families.

For her work, she won the Guggenheim Prize in 1941. Lange used her images to highlight the lives of the forgotten – the poor, sharecroppers, displaced farm families and migrant workers. She distributed her images for free to newspapers, and because of this, she garnered the attention of the national government, which rushed into to alleviate the situation.

After the war Lange joined the staff at California School of Fine Arts (CSFA) as a professor, and co-founded the magazine Aperture. The last two decades of her life, Lange suffered from polio complications, but the reemergence of symptoms hadn’t been diagnosed by doctors so she received no treatment. She died of cancer in 1965.

Lange has been inducted into the California Hall of Fame and the California Museum for History, Women and the Arts. A documentary, American Masters – Dorothea Lange: Grab a Hunk of Lightning, was narrated by her granddaughter and featured journals with never-before-seen photos and interviews that had recently been discovered. A monograph accompanied the release and was the only career-spanning monograph of her work in print.

In 1972 The Whitney museum used 27 of Lange’s photographs from her Japanese internment series. It was titled “Executive Order 9066” because that was the policy number for the document FDR signed, allowing the deportation of Italian, Japanese and German-Americans. It was the first time these images were displayed to the public.

Fun fact: Although Lange won the prestigious Guggenheim award, she turned it down to focus her attentions on the internment of Japanese-American citizens. She focused on the uncertainty of those involved: piles of luggage, families wearing identification tags and everyone waiting for relocation. Her images were so critical that the Army impounded them, and most weren’t seen publicly for 50 years.

The most poignant photograph from this series was of a group of school children pledging allegiance to the flag. It was a reminder to the public that men, women, children and families were being detained without being charged for a crime.