January 6, 2012

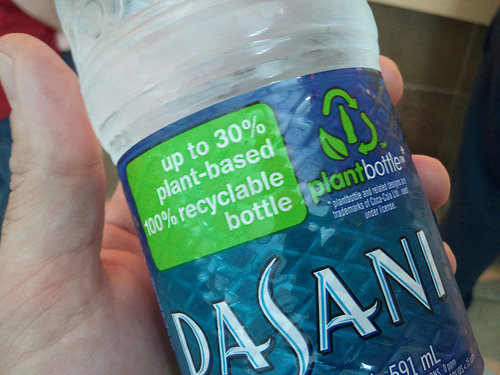

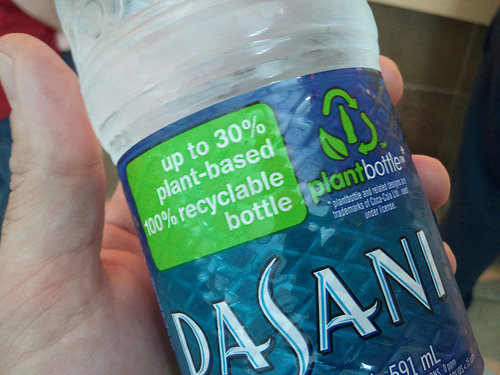

It takes 17 million barrels of oil to produce the amount of bottled water Americans buy each year. Coca-Cola’s brands Dasani and Odwalla, claim to have a solution: plastic made from plants. Sierra Club Green Home decided to find out how these PlantBottles compare to conventional plastics. (Photo by Leonardo Bonanni, Flickr)

[nggallery id=75 template=carousel images=4] [imagebrowser id=75]

By Debra Atlas January 6, 2012

It takes 17 million barrels of oil to produce the disposable plastic water bottles that Americans buy each year. Coca-Cola’s brands Dasani and Odwalla claim to have a solution: plant-derived plastic, also known as bioplastic. Sierra Club Green Home decided to find out how bioplastic bottles compare to conventional plastic bottles in terms of environmental effects.

In 2009, Coca Cola introduced its Dasani PlantBottle, which includes up to 30 percent fiber from Brazilian sugarcane and molasses. Then the company launched its new Odwalla PlantBottle in 2011, the first single-serving beverage bottle made from 100 percent plant-based material. The company says it intends to increase the amount of plant-based material used in its Dasani plastic bottle by utilizing nonfood, plant-based waste such as wood chips and wheat stalks to produce recyclable PET bottles. However, in the two years since Coca-Cola introduced the PlantBottle was introduced, the level and type of plant-based material has remained the same.

Will this move help the giant beverage manufacturer reach its corporate sustainability goals? Or are they merely products wrapped in a greenwashing veneer?

Although these new plastic bottles are made with plant fiber, their environmental impacts are the same as plastics made from oil, according to environmental journalist Amy Westervelt. “They don’t biodegrade, they pollute the world’s oceans and soils, and still leach potentially harmful chemicals into our food,” she says of bioplastics.

What’s more, plant plastics aren’t necessarily free of harmful chemicals, explains Westervelt. A surprising fact about these new plastic bottles is their chemical composition.“The PET resin from plant-derived bottles is identical [to] that of petroleum-based PET [plastic],” says Christina Piles, who supervises the recycling of hazardous waste for the city of Redding, California.

Another of bioplastic is that petrochemical fertilizers are often used to grow the plants that are used to make the bottles, says journalist Mary Catherine O’Connor. And, despite its name, it can’t be composted.

“The compostable plastic industry started making this material without input from the composting industry,” says Will Bakx, co-owner of Petaluma, California’s Sonoma Compost. “They never thought through the lifecycle.”

Although they may not be all Coca-Cola would like you to believe, there are some upsides to these two bioplastic bottles. Both of them are recyclable, although there is some consumer confusion on this matter. And the new Odwalla HDPE (high-density polyethylene) plastic is made from Brazillian sugarcane that is sustainably-grown, rainwater-fed, renewable, and non-GMO. What’s more, using this material doesn’t take anything away from crops grown for human or animal consumption.

That said, if Odwalla’s HDPE bottle is made from such great material, why didn’t Coca-Cola use the same stuff for other beverage bottles? HDPE can’t hold carbonation, so it couldn’t be used for soda, but why not Dasani water?

One possible explanation is the PR benefits of launching two types of plant-based bottles. Perhaps having two bioplastic bottles seems like twice the green effort. Even though “up to 30 percent” plant-based doesn’t sound too convincing, their 100 percent plant-based Odwalla bottle probably scored points with the public.

As we know at Sierra Club Green Home, there’s usually more to the story than meets the eye, and that may well be the case here. Still, if Coca-Cola can come up with the HDPE bottle for one product, why not both?

And if both of these bottles are so chemically similar to petroleum-based plastic, are they really a necessary invention?

For related article, see: Future of Plastic in Plants, Not Petroleum

© 2012 SCGH, LLC.

]]>