Culture August 1, 2019

"I still want someone to read something I’ve written and to think, 'I thought I was the only one.'"

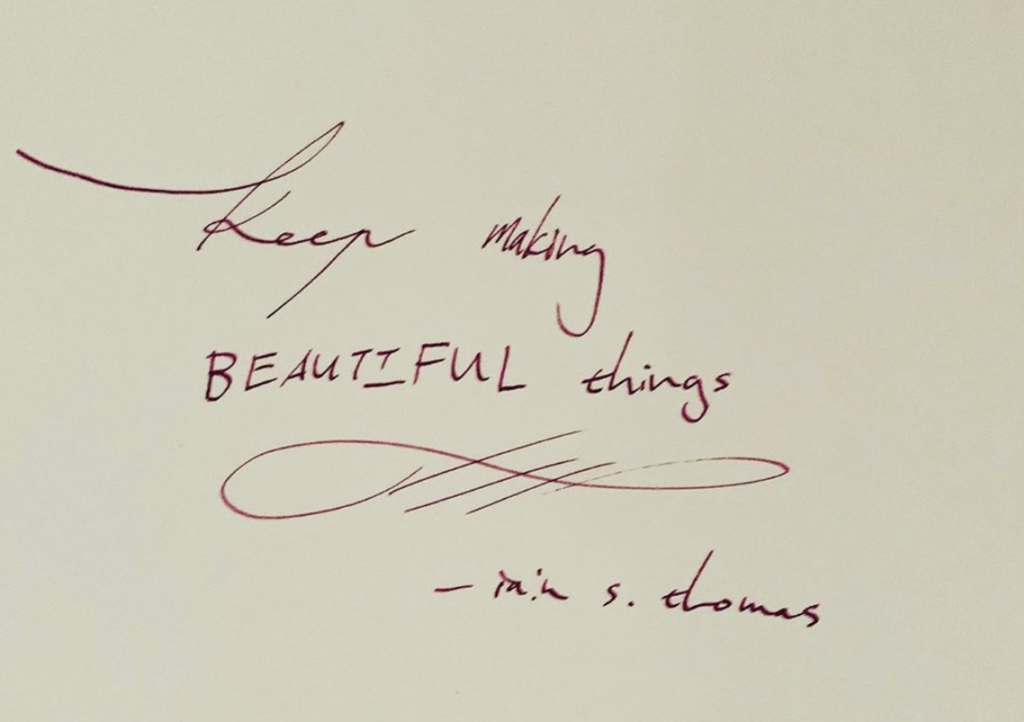

In a world saturated with social media posts meant to garner as many likes as possible, true authenticity is difficult to find. Iain Thomas writes poetry that comes from the soul: it’s poignant, heartfelt, and despite his large following on the site, it’s not created with the Instagram algorithm in mind. I interviewed Iain Thomas about social media, the inspiration behind his work, and maintaining voice in a digital realm. Here’s what he had to say.

I was very lucky when I was young and grew up in a household that had access to the internet, which wasn’t common in South Africa at that point. I developed what I can only describe as a kind of spiritual relationship to it. I was a very introverted kid and I was fascinated by how people communicated in what was a very new space. That sounds strange now because the internet is a ubiquitous thing, and it must sound like someone saying they have a spiritual relationship to electricity or plumbing but at the time, it was something that seemed somehow sacred.

I also spent a lot of time working with designers in my previous career as a copywriter and creative director and I worked a lot on an annual festival of creative thinking in South Africa called the Design Indaba. Through it, I’ve got to meet and interact with artists and designers like Neville Brody, Stefan Sagmeister, Brian Eno and The Campana Brothers. Being exposed to that kind of divergent thinking at a young age was very influential for me.

I don’t have a lot of literary influences.

Fiction wise, I’m reading Stoner and All Quiet On The Western Front. I read a lot of non-fiction and I’ve just finished The War Of Art and Wherever You Go, There You Are.

I’m a little bit all over the place, which is how I like to be. I have a children’s book I’m writing and illustrating called The Secret Of Here, which is about introducing mindfulness to children and teaching them the importance of being present in the individual moments of their life. I have a new collection of prose and poetry at a publisher currently that I can’t reveal the name of yet because it might change, which is based on a series of inkblot illustrations I’m exploring. I’m also developing some smaller books that are focused on individual ideas or poems. Lastly, there’s a spoken word, audio focused project with composer and technologist, BT, that we’re in the very early stages of.

So between all that and my two kids, I never really run out of things to do.

I think it’s important to distinguish between the internet and social media because I think they’re two different things. The internet was incredibly helpful for my career and I wouldn’t be where I am without it. The internet was a democracy of ideas, where if your work or your idea or whatever you were busy with was good enough, an audience would eventually find it.

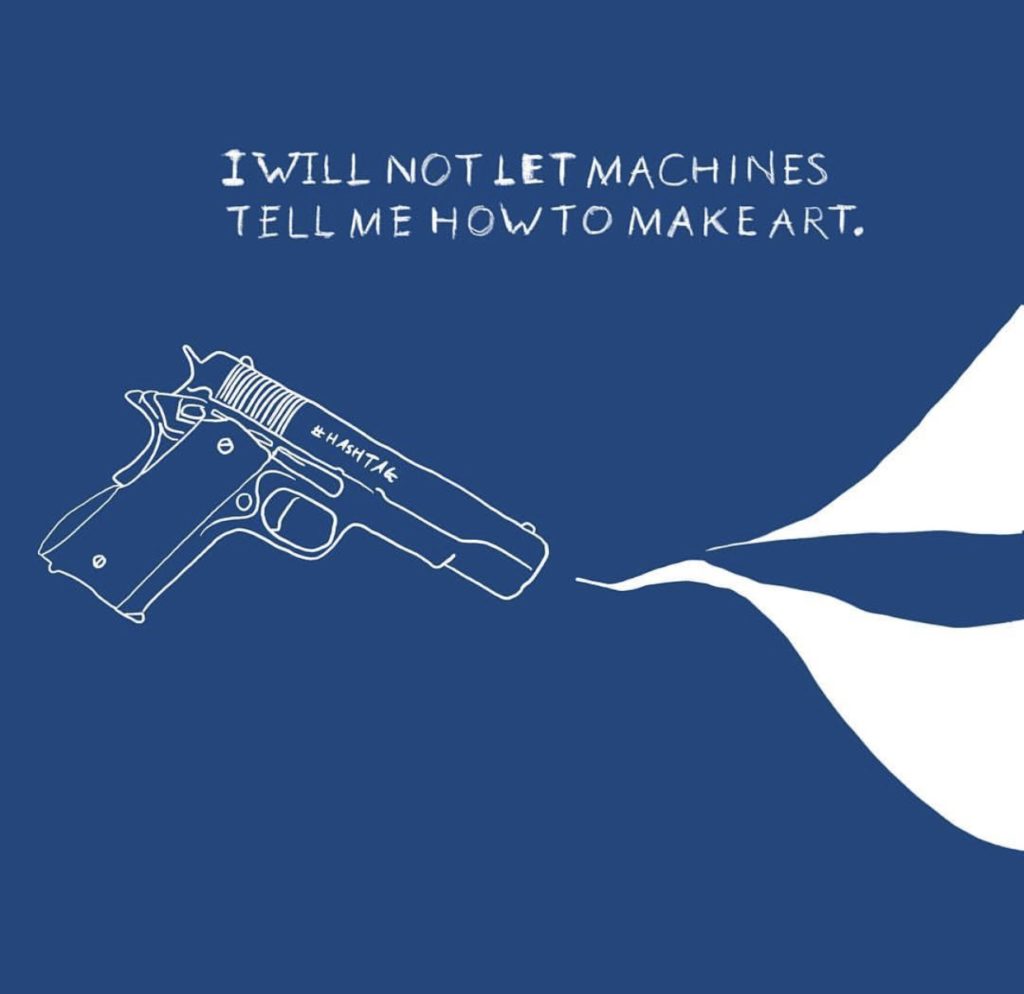

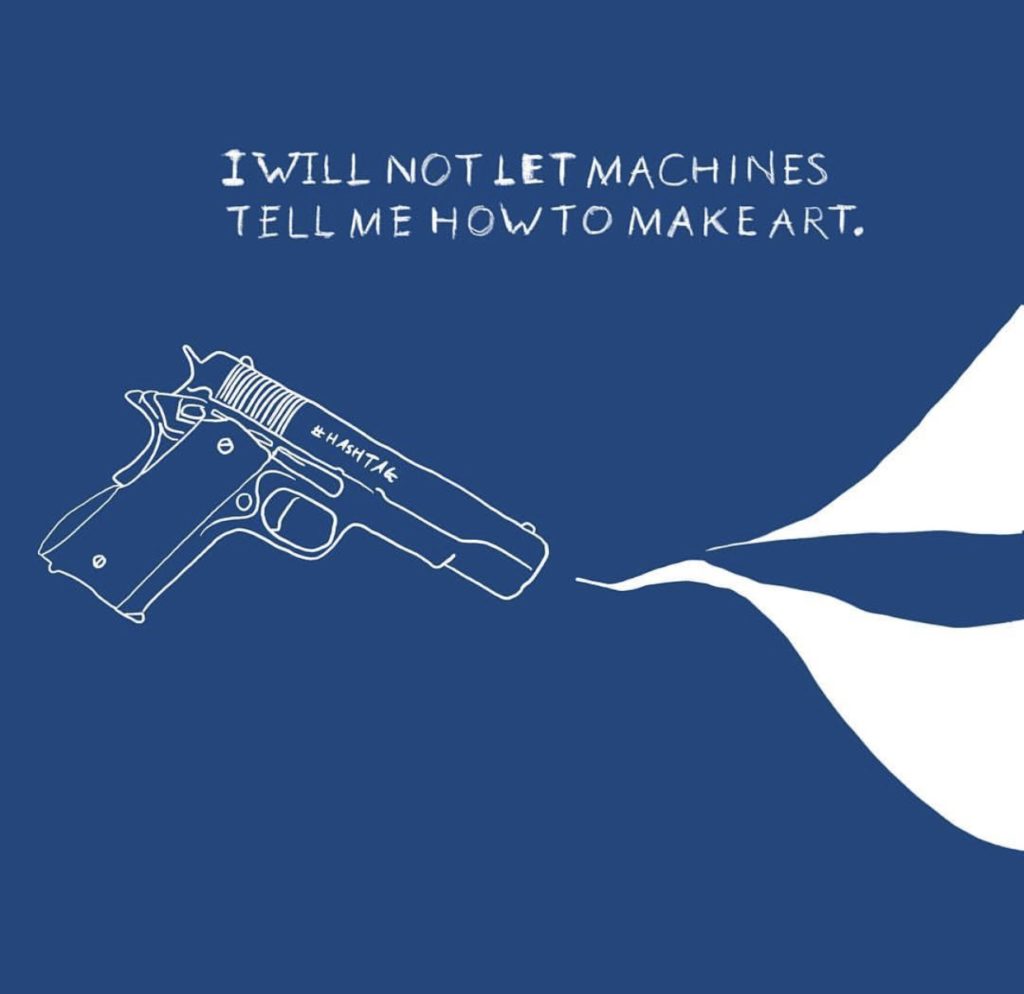

I say “was” because I don’t believe the internet really exists anymore. No one browses the internet anymore. We jump from twitter, to instagram, to facebook, to tumblr to reddit and are ruled by the, to be frank, brutal and opaque algorithms that control those spaces. And if your work doesn’t exist in those spaces, it just doesn’t exist and no one will ever see it. I think those spaces are poisonous. It’s dangerous for a young creative mind to be given a score every single day in terms of how “good” their work is, in the form of likes or retweets or shares. I also think these platforms peddle a dangerous myth that they make it easier for your audience to find your work, when it’s the opposite – unless you pay them, they intentionally make it harder for people to see your work. As a creative person who relies on them to make people aware of my work, I have no choice about being on those platforms. It’s a very uncomfortable situation for me.

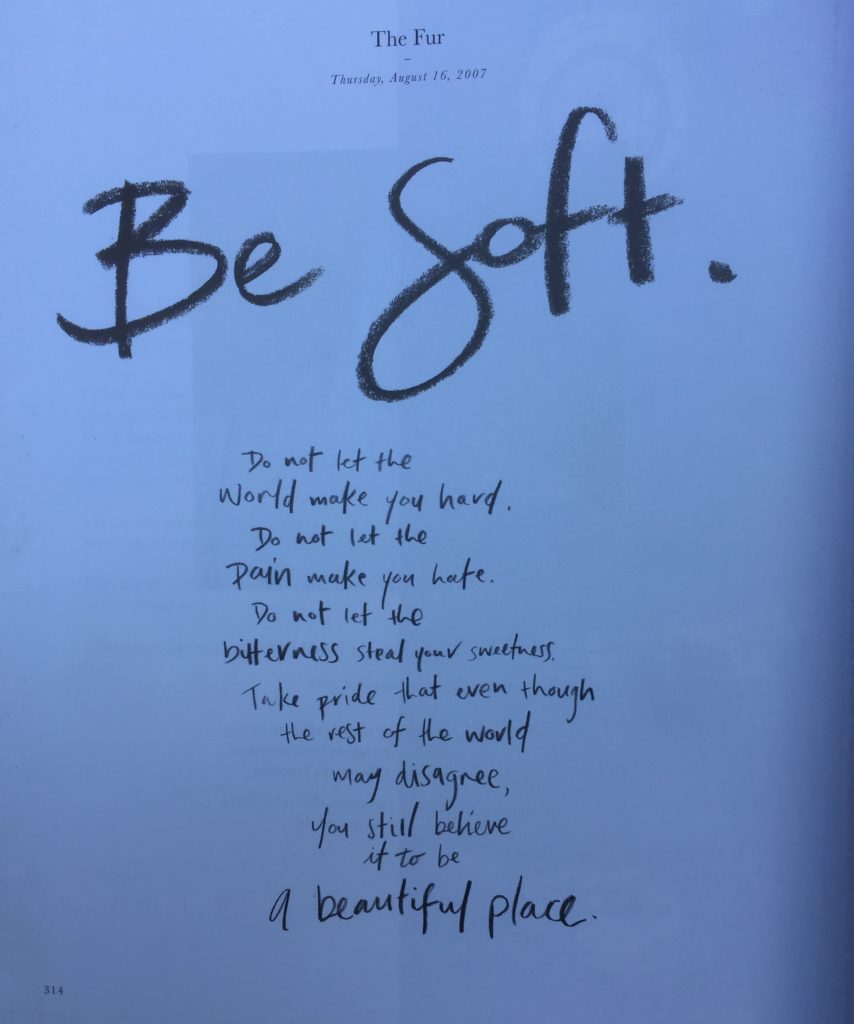

It’s hard. Since I started I Wrote This For You in 2007, there’s a genre of poetry that’s kind of sprung up around it which I find ironic because I’m not even sure what I’m doing is poetry, it just seems to be a handy adjective for my work and tells the people at Barnes & Noble and elsewhere where to put my books. It sent me into a bit of a spiral for a while because I found that the more I tried to stay true to myself, the more I sounded like other people. What I tell myself these days is that people can copy the titles of your books, lines from your prose or the ideas in them, but no one can copy being a better writer and so I focus on that, on trying to learn and on improving my craft.

I’m not sure what to do about it anymore. I think the internet was a large part of what made my voice what it was when I started out but these days, I’m trying to develop strategies and ways of working that allow me to spend less time on it, and that ensure that the time I do spend on it is meaningful.

I think the real danger is that because everyone on social media is consciously or unconsciously trying to satisfy these opaque and arbitrary algorithms, everyone’s work starts to sound exactly the same. Writers learn what topics they need to write about to make the algorithm happy, how long what they write needs to be and what it needs to look like. I think the writers think that they’re responding to their audience but they’re not, they’re responding to the algorithm and so all the work kind of colludes into a banal poetry paste, a kind of tasteless mix of flash fiction about relationships and paraphrased self-help. This is not a unique phenomenon. There are young bedroom producers making tracks at night to satisfy the Spotify algorithm and journalists wording their headlines and articles in ways that they believe the Facebook algorithm will reward. I don’t think enough people are ringing the alarm bell about this but culture is becoming thinner.

I’m afraid that it’s a constant battle. My model was simple in the beginning, I would give everything I wrote away for free and as long as my name, or the name of my project was attached to what I did, it could travel across the internet like a satellite and all of these different satellites would point back to me and help people find the rest of the work and hopefully, buy a book.

That’s changed. A lot of the platforms now are dominated by content farms who steal bits of art and content from across the internet that they then use to get more followers. In turn, access to those followers is sold to advertisers. Instagram and others have no motivation or interest in shutting them down or protecting content creator’s work because ultimately, these content farms make people spend longer on their platforms.

YouTube is in a similar situation. There’s a great video on a channel called “How To Cook That” that explains how some YouTube channels completely make up fantastical sounding recipes just for the ad revenue*. In other words, they’re showcasing recipes for food that cannot possibly be made, to get views. That’s what the algorithms are doing. They’re incentivizing a culture of theft and misinformation.

* https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6abePkXncCM

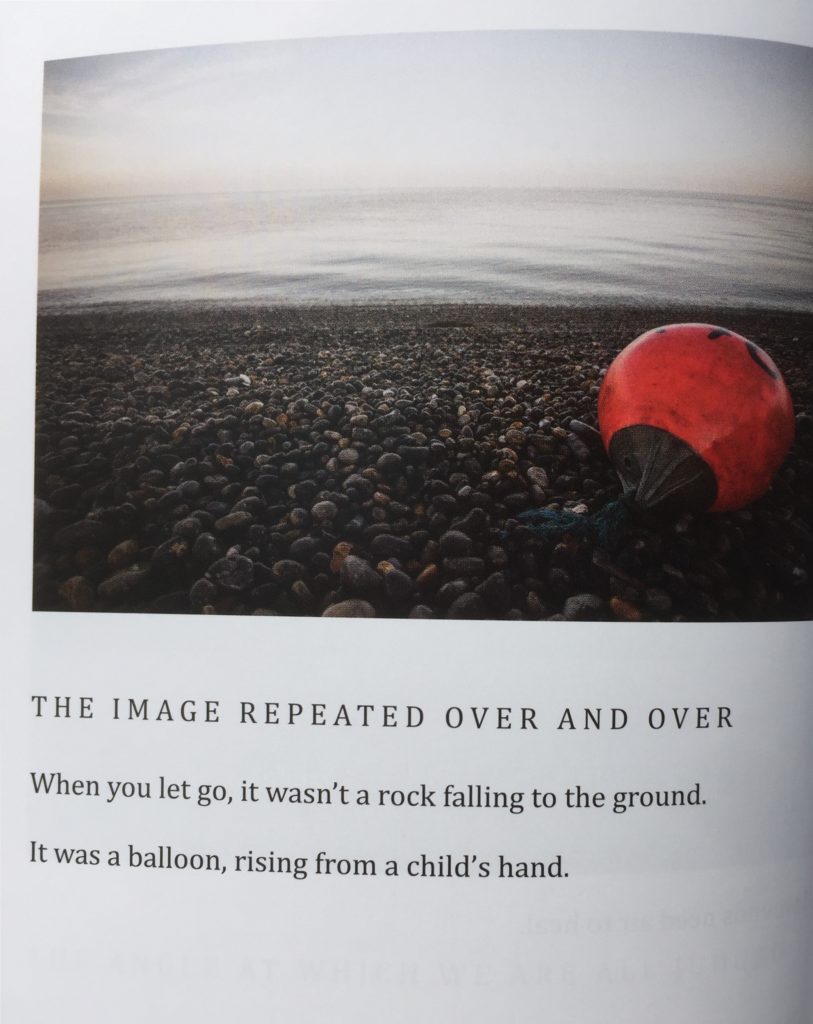

It changes. There’s one I wrote just after my father passed away in 2014 that I’ve been thinking about recently called “The Image Repeated Over And Over” that goes,

“When you let go, it wasn’t a rock falling to the ground. It was a balloon, rising from a child’s hand.”

My father was diagnosed with Multiple Sclerosis the year I was born, so for my entire life, I knew him as someone who was very sick and in a lot of distress. That poem for me is about me coming to terms with his passing, and that in many ways, his death was a release from the pain he was in.

I think so. I used the pseudonym, “pleasefindthis” instead of my real name because I wanted to step out of the way of the work itself and make it all about the reader. But I stopped doing that because people started investing too much power in me and began sending me messages that treated me like I was a guru or a buddha. I started using my real name to divest myself of some of that power. It made the work more potent when I was anonymous but the power imbalance between the reader and me was something that felt quite vulgar, so I started using my real name again. It became important to me that people understood that I was just a person, not some myth or a stereotype ideal of a poet, with a frilly shirt and a bottle of whiskey.

I think the universalness is a direct reaction to growing up in a culture obsessed, in one way or another, with race and classification. At some point when I was young, I realised that we were the bad guys and that I and the people around me had benefitted from the cruel, dehumanizing mechanisms of Apartheid. I never wanted to draw anything from my youth creatively because it felt like the experience was tainted by that event. So I decided to remove all language from my work that described anyone in any specific way, no gendered pronouns, no mention of age, race or location.

I don’t think so. I think that upsets some people because many people want what you might call online prose and poetry to be recognised in that space, and I think it should be, but I just never set out to write poetry, I just wanted to make something different and interesting that connected with people in a meaningful way. Maybe that’s what poetry is but that wasn’t what I was thinking about at the time.

My methods have changed and I’m constantly trying to reimagine what it is that I do, but I don’t know if my goals have changed. I still want someone to read something I’ve written and to think, “I thought I was the only one.”

Follow Iain Thomas on Instagram here.